Would EU citizens prefer to admit asylum seekers or pay other countries to host them instead? A survey experiment

By Cornelius Cappelen, Hakan Sicakkan and Pierre Van Wolleghem, University of Bergen

The two most prominent ways in which EU states can help refugees is by either admitting them as asylum seekers or by providing financial assistance to host countries. But which of these options do EU citizens prefer? Drawing on new survey evidence, Cornelius Cappelen, Hakan G. Sicakkan and Pierre Georges Van Wolleghem demonstrate that support for admitting asylum seekers tends to outweigh support for external financial assistance. – A blog post, originally published by LSE. –

Photo by Levi Meir Clancy on Unsplash

In 2020, the number of people fleeing wars, violence, persecution, and human rights violations rose to nearly 82.4 million people. Oftentimes for mere geographical reasons, large numbers of these people find refuge in developing countries, which, for the most part, lack the means to accommodate and help them.

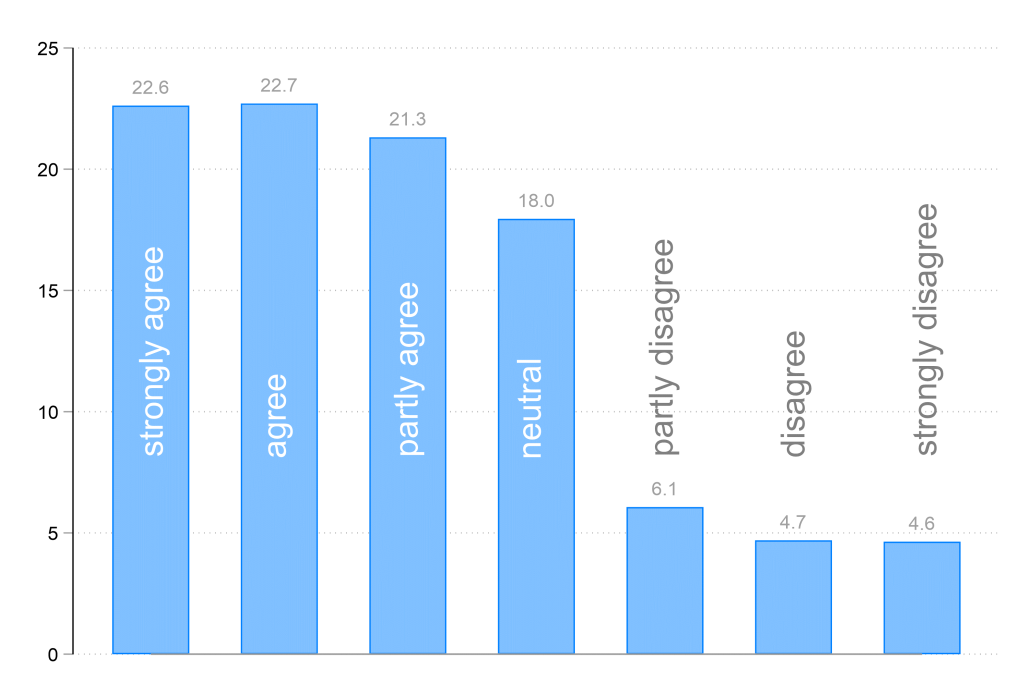

In a world order made up of states, guaranteeing people’s right to seek protection is necessarily a collective effort: states should act in concert to ensure human rights are safeguarded. And citizens from different countries agree with this principle. In a recent study, we asked whether people agree with the fact that all countries should collaborate to protect the world’s refugees. Citizens from 26 countries (21 in Europe plus Canada, the US, Turkey, Mexico and South Africa) massively respond “yes”, with 66.6% tending to agree.

Figure 1: Responses to the statement: “All countries should collaborate and strive by all means to protect the world’s refugees”

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in European Union Politics.

Once we know that public opinion generally supports concerted efforts to protect people in need of protection, the next question is to ask how collaboration should take place.

Fundamentally, there are two broad mechanisms for international responsibility-sharing in refugee matters: the provision of financial assistance to countries hosting large numbers of asylum seekers; and the admission of asylum seekers, most commonly through resettlement. In other words, a country can either provide financial help to ensure other countries can guarantee basic rights and decent living conditions for refugees, or else admit more asylum seekers from countries already hosting comparatively large numbers of them.

The choice for one mechanism or the other is not an easy one; the relocation of asylum seekers has been at the heart of fierce controversies over the last decade. The impossibility to reform the EU’s Dublin system – which attributes disproportionate responsibility to the country which has its border crossed first – is a case in point.

Migration issues have become central in electoral contests in several countries. Therefore, willingly admitting more asylum seekers is highly controversial and risky for politicians – probably more so than paying out financial contributions, unless these contributions are deemed to be too costly.

Paying or admitting? What people think

To shed some light on the leeway governments have on this matter, we sought to understand the kinds of trade-offs that citizens are willing to make when it comes to choosing between these two mechanisms. In our study, we asked survey respondents from each of the 26 countries whether they would be willing to accept a hundred asylum seekers in their country or if they would instead prefer their government to pay another state to accept asylum seekers on their behalf.

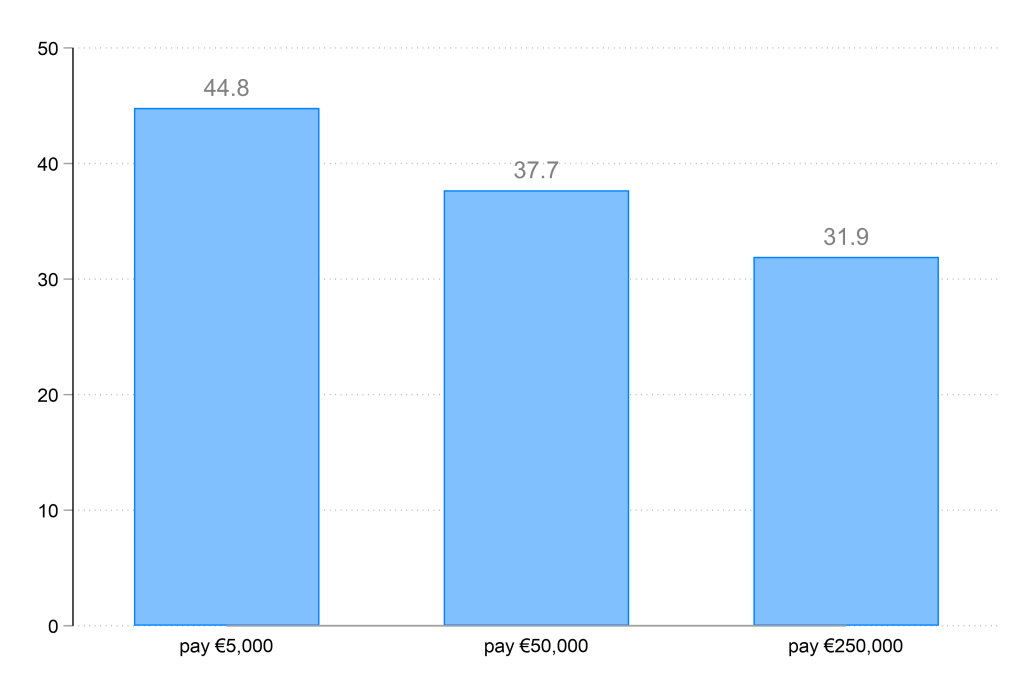

We also conducted an interesting experiment: when asking what respondents preferred, we varied the amount their country would have to pay per asylum seeker for another state to accept them. In this way, we could estimate the effect of the cost of financial contributions. Our respondents were randomly distributed into three groups, with the first group being presented with a financial contribution of €5,000 per asylum seeker, the second one with a contribution of €50,000, and the third one with a contribution of €250,000. Figure 2 illustrates our results.

Figure 2: Percentage of respondents willing to pay another country to accept asylum seekers

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in European Union Politics.

Overall, a sizable majority of the respondents opted for accepting asylum seekers in their countries rather than paying another country to accept them, irrespective of the size of the financial contribution. However, as Figure 2 shows, the higher the amount, the more inclined people were to accept the asylum seekers.

How people choose between alternatives

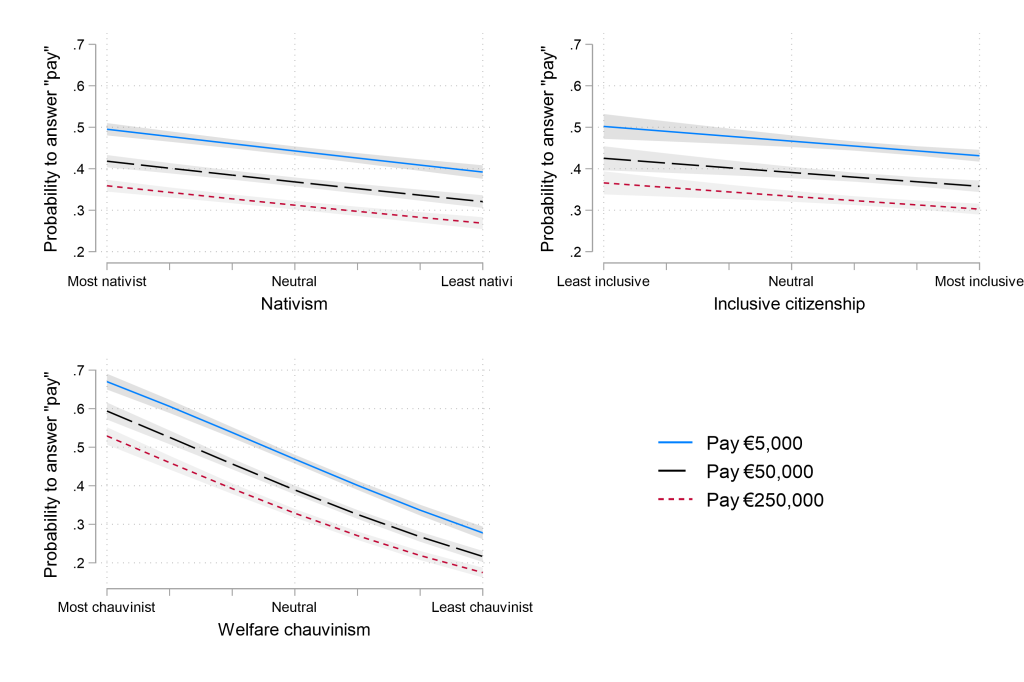

Beyond the economic calculation entailed by the cost of the contribution, we expect people to use cultural and redistributive calculations. People who are more nativist (for whom non-native elements constitute a threat to the community of natives) would thus be less inclined to admit asylum seekers in their country, in accordance with their preference for lesser immigration.

Likewise, people who exhibit a restrictive stance on who is entitled to full citizen rights would be more in favour of paying a financial contribution than admitting asylum seekers. Finally, people who are unwilling to share welfare rights with foreigners residing in their country (so-called “welfare chauvinists”) would also be unwilling to admit more asylum seekers. Nonetheless, cultural and redistributive calculations are also expected to be influenced by the economic calculation linked to the cost of non-admission.

The results of our study are unequivocal: the nativists, those with restrictive views on citizenship, and the welfare chauvinists are more likely to choose paying a financial contribution over admitting more asylum seekers. As Figure 3 shows, the probability of an individual being willing to pay is the highest for the most welfare chauvinist respondents (about 0.68 for the first group of respondents) and lowest for the least chauvinist (about 0.29 for the same group). This indicates people’s attitudes to the redistribution of social rights to foreigners is one of the strongest determinants of their support for financial contribution mechanisms.

Figure 3: Nativism, inclusive citizenship, welfare chauvinism, and willingness to pay a financial contribution to avoid accepting more asylum seekers

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in European Union Politics.

Our research shows that most people support international collaboration to protect the world’s refugees. When it comes to how they would like to implement collaboration, they indicate a preference for admitting more asylum seekers, as opposed to paying a financial contribution. However, this preference varies significantly in relation to the size of the financial contribution as well as people’s attitudes to diversity.

Our findings are highly relevant for policymakers. While EU states have been more willing to curb asylum flows than establish solidarity – as can be seen from endeavours to externalise migration controls to third countries and from the failure to adopt a stable EU-wide responsibility-sharing mechanism – we provide compelling evidence of the sustainability of responsibility-sharing through relocation programmes. Both the UN’s Global Compact for Refugees and the EU’s New Pact on Migration and Asylum call for more international collaboration on protection. Will states heed the public’s preferences and contribute to protect the world’s refugees?

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in European Union Politics

—

Cornelius Cappelen is a Professor in the Department of Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen.

Hakan G. Sicakkan is a Professor in the Department of Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen.

Pierre Georges Van Wolleghem is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen.