While Norway is shaken by the tragedy of Artin, the remains of a one-year-old who washed up on the shores of Karmøy, more than 120 corpses have been washed ashore in Tunisia over a few weeks: the most recent step of a grim procession from Libya toward Europe through the sea. In a trip over April and May 2021, I collected witnesses and opinions from Tunisians and Libyans themselves. Traces of the odyssey are easily found.

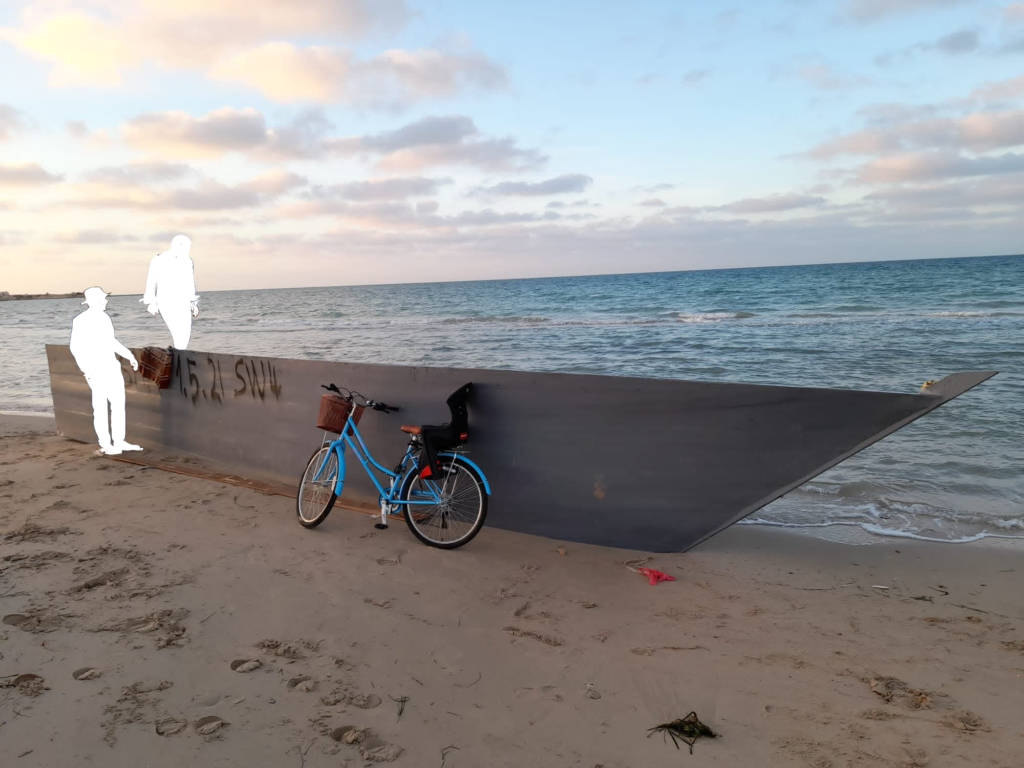

Just in front of hotels shut by the pandemic, a boat appears overnight. ‘You might as well happen to see corpses’, comments a person living nearby. They’re used to it. Mohsen Lihidheb, a local who created a ‘migration museum’, recites before me a poem about the first time he heard a dead ‘knocking’ on the cliffs beneath him.

Over the year he has collected more than 6000 shoes on the beaches. He is certain they belong to harraga. Yet this year the flows are swelling: so many newcomers, so many about to leave. I chat with a cleaning girl just outside another empty hotel: she’s from Subsaharan Africa, and asks me where I’m from: ‘Italy? I’m about to go there!’ she smiles enthusiastically. A fortnight later I see the hotel owner: ‘Two of my employees have left to the sea’ he complains.

‘I’d never trust the smugglers’

A Tunisian taxi driver starts from a similar point: ‘You’re from Italy! I’ve been there as well! The crossing is easy, I’m a fisherman.’ He proudly shows me pictures of his sons: they’re both in Europe ‘Weren’t you afraid for them? Isn’t it dangerous?’ ‘Yes, a bit, but you have to take risks in life. Anyway, here we have no future. Do you know how much I paid for this second-hand car? If I work the whole day, subtract the gasoline, and I’m left with a small tip. How can I support a family of four? Prices have gone up, salaries are the same, actually many lost their jobs when terrorist attacks and then COVID drove tourists away’.

A neighbor confirms: ‘Before, our problem was: they [politicians] steal, but I eat. Now, they’re still stealing, and my plate is empty’. They wait for the Arab Spring to deliver on its promises after a decade, and the anniversary is marked by protests as well as by celebrations.

This young man has worked in tourist places in Europe. He speaks some four languages, but COVID forced him back as these were deserted. His story is not unique. Remittances went down by one fifth in 2020, the sharpest shrinkage in history: they’re still 14% lower than before the crisis in 2021. This means millions are left without means of subsistence.

‘The route is not that dangerous for us Tunisians. The worst that usually happens is they send you back. But I wasn’t treated badly. I would not leave from Libya, however, that’s reckless. ‘I’d rather join a militia than leave with a boat’ a Libyan confirms to me. ‘I’d never trust the smugglers, they torture, they rape, they throw you in the sea if that’s advantageous.

The people in power in Tripoli know them: they know their names, where they live, everything! But they cannot stop them. Our coast is 1.100 miles: now is out of control. The state is in pieces. Tens of thousands are ready to leave: Italy and Europe should prepare for the summer!’ He laughs bitterly.

‘We need peace’

Libya’s path to peace goes through this year’s elections: I ask another Libyan, the first-born of a prestigious Bedouin family, whether the country will be stabilized and united from December. ‘Maybe’ he remains detached. ‘We need peace. Kids enroll in militias every day. They wear shorts and hold Kalashnikovs, stop cars on the highway, and ask for a ‘toll’. People are fed up after a decade of fighting. We have foreign powers and interests all over, but under the surface, Libyans are like this [he makes the sign of a knot with his hands]’.

His views resonate with analyses explaining Libya’s catastrophe in the light of regional and global powers’ ‘Lust for Libya’. But keeping foreign interests out of a country with immense resources and one of the earth’s lowest population densities (221 out of 232) is a titanic task.

Italy’s relation with Libya, which was seen as a ‘fourth shore’ in colonial times, is finally informed by concerns for the Libyan people and by Italy’s European identity. At the same time, migrants from the Southern Mediterranean dream of safety and prosperity in Europe. After all, the two coasts hang on to the same floating ideal, but with very different reasons and risks involved.

On the Northern coast, at least one can hope a peninsula will not sink.