By Erlend Paasche (Vulner project), the Norwegian Institute for Social Research. Photo: UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe

World Refugee Day is a good day to reflect on refugee resettlement, a distant dream for most of the world’s refugees. It is defined by the UNHCR as ‘the selection and transfer of refugees from a state in which they have sought protection to a third state which has agreed to admit them–as refugees–with permanent residence status’. As one of the three durable solutions next to return and local integration, it is designated for ‘the most vulnerable’. Overall, less than one per cent of the refugees under UNHCR’s mandate are ever resettled.

A Somali refugee stands inside a tent with her baby in Dollo Ado, Ethiopia. Fleeing drought and famine in their home country, thousands of Somalis have taken up residence across the border in Dollo Ado where a complex of camps is assisted by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). Photo: UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe. www.unmultimedia.org/photo/

In theory, resettlement is quite straightforward. For EU+ member states, resettlement starts with a request from the UNHCR based on the need for international protection of a third-country national or stateless person from a third country, and ends when the state accords refugee status within the meaning of Art. 2 (d) of Directive 2011/95/EU (Recast Qualification Directive).

In practice, resettlement is a complex, multi-level form of governance in which ‘vulnerability’ is bureaucratically constructed by a plethora of actors, including refugees themselves, throughout the following four idealized stages.

First, vulnerability is performed by refugees. Vulnerability can, ironically, be a resource, in the sense that it can unlock the option of resettlement. While it does happen that refugees decline offers of resettlement, this is exceptional. As a general rule, the high demand for the very few resettlement slots available make these slots extremely valuable commodities.

The scarcity incentivizes the performance of vulnerability among refugees and the strategic crafting of refugee narratives, while the UNHCR also observes that ‘the most vulnerable are sometimes the least visible and vocal’.

Assessing vulnerabilities

Second, refugees’ lived vulnerability is sifted by the UNHCR into its seven submission categories: Legal and/or Physical Protection Needs, Survivors of Torture and/or Violence, Medical Needs, Women and Girls at Risk, Family Reunification, Children and Adolescents at Risk, and Lack of Foreseeable Alternative Durable Solutions.

The UN agency describes this process of ordering vulnerability as ‘an ongoing, active and systematic process (…)’. Yet resettlement states rarely trust it entirely. Few base their resettlement on UNHCR-referred dossier cases alone.

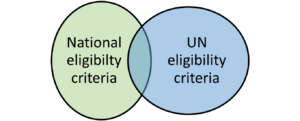

Third, then, comes another round of interviews in which refugees demonstrate and perform their vulnerability in front of a new audience of national selection missions. Resettlement states often seek to make their own assessment of vulnerability and other dimensions, such as security, and apply their own additional eligibility criteria.

National eligibility criteria vary widely, but some demographics (e.g. not-too-large families with small children) are generally seen as more desirable than others (e.g. single men), and some demographics (e.g. very large families with adult children) face particularly slim odds. Some (e.g. conservative Syrian Muslims) are, ironically, particularly vulnerable to being securitized as threats and not resettled on those grounds.

Resettlement in the intersection

Carving out a new life in a new country

Fourth, upon resettlement, a chosen few refugees carve out their new life. For some, vulnerability was more situational, even if it may have long-term effects. For others, including many of those with chronical illness, vulnerability is more innate but possibly less incapacitating now. For others yet, vulnerability is administratively induced through resettlement itself.

All of a sudden, families from rural areas who have never used electricity or a bank card now find themselves stripped of social support networks and location-specific capital, mired in the anxieties of a liquid modernity that is utterly alien to them. Integration outcomes, needs and vulnerabilities of resettlement refugees may in turn be quantified by local authorities and reported to central authorities, potentially feeding into future quota composition.

The complexity of the operation is compounded by the task of balancing vulnerability against other concerns, such as presumed future integration. My co-authors and I analyze this in a recent report. How vulnerable is enough? How vulnerable is too much?

A certain pragmatism ensures the sustainability and ongoing popular support of the resettlement programme. Yet veer too far into a pragmatic logic and the ‘most vulnerable’ will be screened out in what effectively becomes a mechanism for labour migration. Idealism must be tempered by pragmatism, but only up to a point.

Two directions for future research on resettlement

Cherry-picking the best educated and most adaptive refugees for resettlement would not be unlawful because resettlement is primarily a discretionary practice, unlike the asylum system, but it would undermine the programme’s humanitarian objectives, do irreparable reputational damage to the UNHCR and erode the cornerstone principles of burden-sharing and refugee protection.

For researchers, this skeletal outline suggests at least two directions for future research.

One is the perspectives of resettlement refugees themselves on resettlement. How do they see their vulnerabilities, the selection process, and the costs and benefits of resettlement?

The other concerns the programmes’ political ascendancy. The international protection regime is undermined by non-admission policies, deterrence measures and the extraterritorialization of border control. Whether resettlement is on the rise because of this or in spite of this is a thorny question, but one that needs to be addressed.