The continuum of violence and death on the Greek island of Lesvos

By Evgenia Iliadou, University of Surrey

One cold December morning on Lesvos in 2012 I woke up from the sudden ring of the phone. The sad voice on the other side of the line was urging me to wake up and help: “The sea has washed ashore dead bodies!” said the voice, who belonged to one of the members of the local activist network I was involved with, and then burst into tears. A fatal shipwreck had taken place in the early hours off the coasts of Lesvos. Refugees’ dead bodies were found by locals, frozen on the coasts’ pebbles near Mytilene, the centre of Lesvos Island’s capital. Dead bodies, shoes, clothes, and various objects were scattered here and there reminding of a battlefield in a time of peace. These were the discarded bodies and belongings of those who were not allowed to belong. A member of the rescue crew told me that day that from the position in which the dead bodies were found on the shore, one could tell that some of the border crossers had reached Lesvos alive but had eventually frozen to death. The frozen death found them on the threshold of Europe.

Since early 2000, I worked as an NGO practitioner in refugee camps and detention centres by providing social support to forcibly displaced persons. I worked in many different sites of confinement in border zones in the Greek mainland and on the islands, notably in Lesvos. I was also actively involved in grassroots movements supporting refugees who were reaching Lesvos for more than a decade.

Those experiences were often shocking, traumatic, and life-changing as over time and through my different positionalities (a female researcher, former NGO worker, activist, local) I had the chance to witness first-hand the harmful and life-threatening conditions in which refugee populations were forced to live inside detention centres and refugee camps. The living conditions that refugee populations endured were appalling and tantamount to cruel, inhumane, and degrading.

Over time I heard and recorded several accounts and testimonies by refugees related to border violence, including torture, sexual violence, human trafficking, state violence, and pushbacks.

Violence continues after the border is crossed

Since the 1990s, Greece generally, and Lesvos island specifically, have been important gates for forcibly displaced people who are fleeing violence, conflicts, wars, and persecution. Ever since people have been dying while crossing the Greek-Turkish border, and their lifeless bodies wash ashore.

The Aegean Sea has become a tool of boundary enforcement and a strategic slayer of border crossers. It has also become a liquid graveyard wherein the politics of death has found its ultimate materialisation.

Although represented as new, random, unforeseen, unpreventable events and “tragic” accidents, border deaths are the outcome of a series of lethal political decisions, deterrent policies, and practices, which have been enforced since the 1985 Schengen Agreement, and have greatly proliferated in the aftermath of the 2015 refugee crisis.

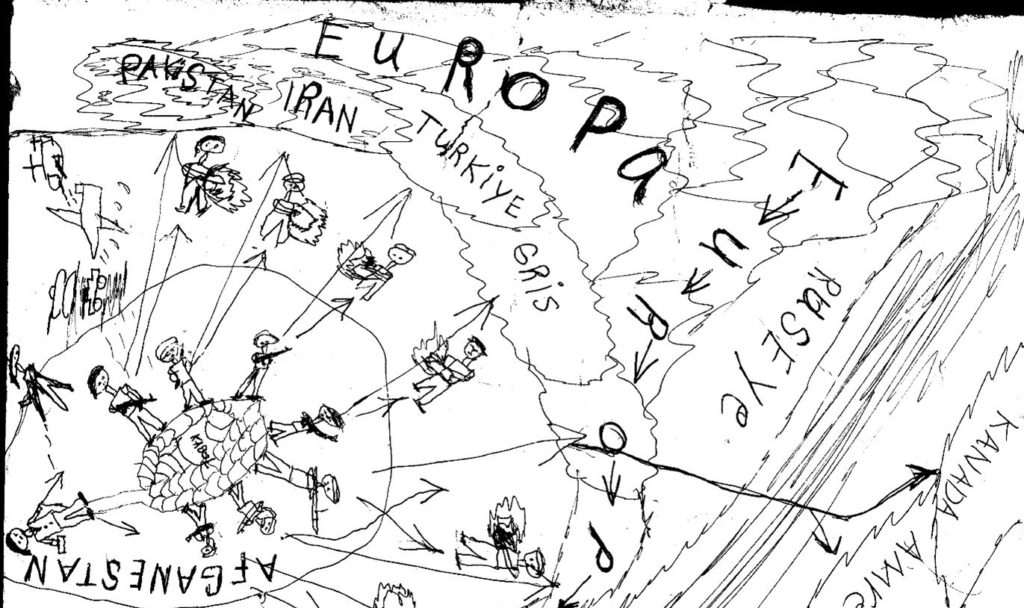

Violence in the countries of origin depicted by refugees detained on Lesvos, 2008-2010/ copyright E. Iliadou

Violence is multilayered and systematic and is routinely inflicted upon refugees from their countries of origin and continues while refugees are en route and traverse the multiple land and sea border pathways which lead to Europe.

Violence is inflicted through multilayered, deliberate deterring-killing policies and practices, actions and inactions – by state officials and border agents – of exposure and abandonment of refugees to death or an increased risk of death.

Through political decisions, search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean and Aegean Sea, everyday acts of solidarity by NGOs, citizens, volunteers, and solidarity networks are systematically prohibited and prosecuted. This condition is often referred to as criminalisation of solidarity.

Furthermore, deterring-killing policies are actualized through push-back operations combined with intimidation, torture and other forms of physical abuse, as well as left-to-die practices and abandonment of refugees in distress to the sea, where they experience extreme environmental conditions, dehydration, and are eventually exposed to death or to an increased risk of death. In the aftermath of the so-called 2015 refugee crisis, violent push-backs have become the norm in the Aegean Sea.

However, violence continues after the border is crossed and even when refugees manage to reach Europe alive. Deaths, fatal injuries and accidents continue taking place inside refugee camps and detention centres. Due to the abandonment of refugees in life-threatening conditions with inadequate reception and accommodation facilities, healthcare and medical treatment, social and psychological support, refugees die in camps or face an increased risk of death.

When I was conducting my fieldwork, only within one week, three refugees died of fumes in their tents in the Moria camp, which was the main refugee camp on Lesvos island. Since then, social suffering and deaths in camps routinely take place and have been normalised. Refugees are abandoned by law and this abandonment and normalisation is epitomised in what Alex, an informant from Afghanistan, told me:

“Poor refugees, they travelled from so far away in order to reach Europe, but only to die alone in their frozen tent. Moria should not be called a refugee camp. It should be called a graveyard.”

Border violence depicted by refugee detained on Lesvos in 2008/ copyright E. Iliadou

The violence continuum beyond death

Although one might think that death would be the last act of a lethal political game which is played at refugees’ expense and that death itself would serve as a figurative border beyond which violence would not carry on and inflict suffering.

My research indicates that violence also continues in death and even beyond the moment of death. Violence continues to be inflicted upon the lifeless bodies which are washed ashore, the unidentified and missing persons, the shipwreck survivors, the families, and even whole communities.

After the event of death, the living – survivors, families and whole communities – must adhere to the rules of a dysfunctional bureaucracy which is underpinned by multiple, lengthy, inconsistent and parallel procedures and sub-procedures. This is because there are different procedures in case dead bodies or human remains are recovered, if a person renders missing, if there are relatives and/or survivors who can identify the bodies and different procedures in case the bodies are rendered unidentified.

Even though deaths have occurred at the Greek-Turkish borders for more than two decades, there are no standardised procedures and guidelines for the aforementioned processes to take place. The lack of standardised procedures and guidelines have produced a policy vacuum, which itself produces more suffering upon survivors, the families, and even whole communities, who are stuck in a temporal limbo without knowing what to do.

Due to the lack of interpretation services, socio-psychological and legal support for families, who in many cases are themselves survivors of the same shipwreck as well as witnesses of the death of their loved ones, the identification and bureaucratic procedures can take considerable time. Also, the identification procedures are carried out by the authorities immediately after the event, without survivors’ and families’ grief to be considered or respected.

Shipwrecks survivors are often detained or accommodated in degrading and life-threatening conditions inside refugee camps. Frequently, identification of the dead is not successful due to the lack of evidence, the decomposition of bodies or the remains, as well as the expensive and lengthy procedures in finding and bringing the relatives for identification.

Due to the dysfunctional bureaucratic system surrounding the dead or missing, the quest of tracing refugees becomes agonising, but mainly impossible for the relatives. Often, relatives are reaching the Greek islands by being (mis)informed or deceived by smugglers – who themselves take advantage of the system’s gaps and inconsistency and profiteer from relatives’ pain.

The lack of consistency of post-mortem data, maps, and records of the graves in the cemetery prevent the relatives from tracing the grave and exhume and repatriate the body.

As a former practitioner on Lesvos, I witnessed myself families wandering from island to island and from port police to port police station looking for their loved ones by the means of photos, clothes, shoes, personal belongings, marks on the skins, and tattoos. The pain of this quest exacerbates in cases where families manage to detect their relatives, but when they do, it is too late. The body is already buried as “unknown”.

The missing cannot be grieved and buried

The performance of burials and rituals is another painful process. The cemetery which has been used after 2015 is an allotment which is rented by the Lesvos’ municipality and managed by activists and refugees.

Both attributes – “cemetery” and “religious leaders” – are not formal since the cemetery operates without a legal license and is temporal, while the religious leaders are two volunteer refugees who have become experts by experience in completing the funeral rites and rituals.

The religious protocol and rituals, which include cleaning and caring for the body before it is buried, its position within the grave, and the choice of the grave’s direction, often takes place inappropriately and rashly, due to the limited refrigerator facilities available in the morgue, and the limited period during which the bodies could be stored in them.

As such, often the performance of a culturally appropriate burial and ritual procedures cannot be guaranteed, and the dignity and memory of the dead could not be respected. Burial procedures and rituals are of social, cultural, political, and emotional significance for the families and the whole communities. The funeral rituals are a way of strengthening the social bond.

Without a proper burial the rite of passage from the world of the living to the world of the dead cannot be fulfilled. Therefore, the soul remains in a liminal temporal threshold between earth and afterlife – a condition which Hertz describes through the metaphor of the “unquiet dead”; a soul which can never rest and is condemned “forever impinging on the land of the living”.

The anthropologist Mary Douglas in her work showed that the absence of death rituals signifies the disruption of social order – a danger, pollution, and impurity which is transmitted upon by contaminating the living and the communities.

The violence continuum is exemplified in the figure of the missing and unknown person who stuck within a liminal temporal threshold between life and death. Missing people cannot be grieved and buried, but they cannot also give relief to the living, who are (a)waiting for news, and questing of the traces of their loved ones.

This quest can last for months, years, and even a lifetime. Families and communities cannot perform the rituals, the last parting words are never told and the rite of passage from mourning to closure cannot be fulfilled. The healing process is temporally frozen, and grief becomes protracted and complicated, loss remains unclear, unresolved, and ambiguous.

Death is not the end but the perpetuation of violence

Despite the current hypervisibility of push-back operations, border deaths and violence in the Aegean Sea, violence has deep historical roots. Violence exists historically, continues, unfolds, and escalates cumulatively across time and space. Its impact upon refugee populations intensifies, deteriorates and becomes greater over time by inflicting social suffering and multiple forms of harm, and death.

These harms are experienced as if they interact, combine, and intersect by exacerbating and producing more and/or new types of social suffering and harm.

The aforementioned thanatopolitical border regime violates the inherent right to life embodied in article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and articles 2, 4 and 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

The right to life is the most fundamental human right which is applicable without any discrimination, at all times and in all circumstances. It is the basis of all other rights, since any attempt to safeguard other rights is impossible if the right to life is not protected.

However, the systematic and deliberate disregard of life through pushbacks and left-to-die deterrent border practices by state officials violate the right to life itself. They consist of crimes of act and, hence, they are state crimes.

Push-backs are also arbitrary according to the international law since they breach the principle of non-refoulement. Moreover, the duty to rescue persons in distress at sea is a fundamental rule of the international law of the sea, maritime law and international humanitarian law.

The left-to-die practices by state officials are arbitrary, consist of infringement of duty, and violate the 1974 International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), and the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Finally, the mundane practices and policies in respect to the post-mortem corporal mistreatment of the dead, the performance of undignified and culturally inappropriate burial procedures and rituals, and the lack of memorialisation insult the memory of the dead and inflict cultural violence and suffering to the dead, which transmitted upon the living and whole communities.

Therefore, death itself does not signify the end, but rather the perpetuation of violence and social suffering upon the dead, the living and whole communities for an indefinite period of time.