Academics & the Media: Taking on the Expert Role – with Simon Usherwood

He spends weekends preparing in-depth analyses of the latest Brexit developments for his 20 0000 Twitter followers and is frequently consulted by some of the largest global news outlets. What motivates Professor Simon Usherwood to take on the ‘expert role’ week after week on social media and in the media? – If we don’t try to help inform debate, then others will fill that gap, and not necessarily to the same standard.

Simon Usherwood is Professor of Politics at the University of Surrey, UK, and one of the leads on PROTECT’s dissemination and communication work.

In addition to his scholarly activities, teaching, and researching, Usherwood keeps tens of thousands of Twitter followers updated on the Brexit process through sharing in-depth and visual analyses in blogs, vlogs, and in global news outlets.

Why bother, you may ask?

– For me, a key part of being an academic is about being part of the wider community, helping others to make sense of what is happening around them, and supporting them to make informed decisions about their lives, Usherwood explains.

– One of the best ways to get out to a large audience is via the broadcast and print media, even if it does mean you’re not quite so much in control of the message that goes out: that balance between being able to get deep into an issue and reaching many people is one that has to be acknowledged and reflected upon each time.

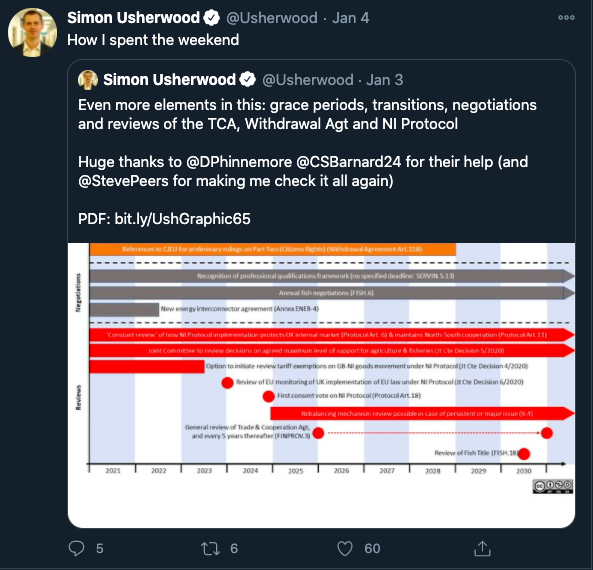

Sharing graphics on Twitter: Graphics showing Brexit timelines, developments explanations, and more is a familiar sight to Usherwood’s Twitter followers. This graphic presents a timeline for the EU-UK trade & cooperation agreement, its grace periods, and provisions, whereas another recent graph showed the further legislative steps the UK has to take in its preparations to leave the EU.

Helping to make sense of it all

Combating disinformation and creating an informed public debate are key elements of Usherwood’s motivation for public engagement.

He encourages other academics to take up more space in the media landscape:

– Our expertise and understanding is something that can help others and, importantly, can be a counterweight to both the uninformed opinions of some other commentators and the disinformation of others. If we don’t try to help inform debate, then others will fill that gap, and not necessarily to the same standard.

– This is something that should be part of many more academic colleagues’ lives: very often I meet colleagues with a sharp and incisive understanding of an issue, who are reluctant to engage with ‘the media’, he says.

The expert is not on anyone’s side

When appearing in the media, researchers are often featured as the ‘expert source’ – a label well-suited for academics claims Usherwood:

– The label of ‘expert’ has been a particular issue here in the UK in recent years, following the Brexit referendum. Yes, it can be used to try and brush you aside, but much more commonly, it has proved to be a useful way of showing that you’re on anyone’s ‘side’ in a debate, he says.

– The natural tendency of academics to reflect on what they do (and don’t) know, to weigh evidence, and to be in the habit of communicating to others in teaching: all of these make us well-positioned to engage with the media and social media. Stick to what you know, treat others with the respect they deserve, and help to make public debate something a bit better than it was. It’s much better than just shouting at the news!

Reaching thousands: Usherwood was recently featured in a video blog (vlog) on the UK’s exit from the EU, produced by the independent Brazilian news platform Headline. The video received nearly 9000 views.

Negative experiences causes media reluctance

Professor of Sociology at the University of Oslo, Mette Andersson, has studied migration researchers’ experiences with the media and concludes that the boundaries between research, politics, and science seem to dissolve when researchers within highly sensitive or polarized fields offer their expert opinion in the media.

Such researchers may therefore risk reaping severe negative reactions when appearing in the media, as the public often assigns them with a political view or agenda.

In December 2020, after the UK Parliament approved the Brexit deal, Usherwood commented on its historical significance in Al Jazeera.

Professor Simon Usherwood understands fellow academics’ potential reservations:

– Certainly, in some cases, colleagues’ reluctance to engage with the media is a result of bad experiences: social media can be particularly fraught if someone decides to take against you, especially if you represent a minority group, says Usherwood.

He does not, however, believe that receiving public criticism and negative reactions is the norm when interacting with the media:

– The very large majority of journalists that I’ve spoken to has been genuinely keen to talk with someone who knows what they’re talking about and who provides evidence to back up their claims. In addition, if your contribution is about setting out the facts, rather than being an advocate for a particular course of action, then that can forestall much of the criticism, he says.

Informing the public: three lessons to take away from the Brexit process

In a recent PROTECT blog, Usherwood wrote about the art of connecting ongoing research to ongoing debates. He highlights three lessons from his Brexit engagement:

– Firstly, academic input is valued in such debates. Academics are one of the most trusted groups in society, both in the UK and beyond. That trust is grounded in the values that so define our profession: being led by evidence, not dogma; encouraging debate, and; a constant re-checking of what we know, he says.

However, the media and the general public are not the only bodies of society that academics interact with, or provide advice to. Policymakers and governments too might seek their advice. This is why researchers must learn to adapt their research output to meet the needs of different audiences, says Usherwood:

– A civil society organization might want to understand the processes of government policy-making, while the government itself might be looking for overviews of the effectiveness of different options, and the media need a one-minute clip to be part of their rolling coverage. All are legitimate uses of research, but each requires a rather particular set of skills to produce, he says.

The Brexit Club: Usherwood is part of the University of Surrey’s weekly concept, the Brexit Club, where he dives into the weekly Brexit developments. His cat Bean frequently contributes with groundbreaking analyses – and company.

– Academics need to recognize that if their work is to be of real use to users, then they have to think about those users’ needs when engaging with them. This includes reflecting on the level of fine detail that’s needed, the use to which it might be put and the time-frame available for all this. Academic work is important in its own right, but that doesn’t mean the world runs to its timetable.

– Stakeholders can drive research too

The third lesson from Usherwood’s Brexit engagement is to recognize the importance of dialogue and seeing public engagement as a one way-street:

– There has to be a feedback process, the academic cannot simply present their findings and then leave everyone else to it, to work out what to do with it all, he says.

– Part of that is about understanding how research fits into the practical world that it might seek to inform: if we understand better what stakeholders might do with our work, then we might better be able to give them more of what they need, Usherwood concludes.