Relocating asylum seekers or paying someone else to do it for you?

What citizens have to say

by Cornelius Cappelen, Hakan Sicakkan and Pierre Van Wolleghem, University of Bergen

Relocation of asylum seekers has been at the heart of fierce controversies over the past decade. Governments’ worries over migration is not a new phenomenon insofar as migration has become a subject of electoral competition, a topic on which one gains or loses votes, and perhaps even elections. That being said, migration and asylum are two distinct policy issues and public attitudes towards migration and towards asylum may very well differ, as recent scholarship suggests. This blog-post poses a series of questions that Cornelius Cappelen, Hakan Sicakkan and Pierre Van Wolleghem tries to answer through a survey conducted in the framework of WP6.

Photo by Martin Krchnacek on Unsplash

The refugee crisis and limits of EU solidarity in asylum matters

Relocation of asylum seekers has been at the heart of fierce controversies over the past decade. When the refugee crisis erupted in Europe in 2014-2016, the large inflows of asylum seekers shed light on the inadequacy of a system that everyone knew to be wobbly: the Dublin Regulation. Said Regulation aims to determine which EU member state is responsible for a given asylum claim lodged in the block. It relies on a hierarchy of principles that most often ends up in attributing responsibility to the member states whose border has been irregularly crossed. For mere geographical reasons, the states that happen to be located at the external borders of the EU are the ones bearing much of the responsibility. While this system somehow works so long as influxes are low, the sizeable increases of the years 2014-2016 clearly unveiled its limits; with Italy and Greece struggling to deal with the situation and calling for solidarity from their fellow member states.

Mandatory solidarity and the impossible reform of the Dublin system

The uneven distribution of large influxes of asylum seekers created tensions between member states. In 2016, the European Commission tabled a reform of the Dublin Regulation that provided for the creation of a permanent and mandatory relocation mechanism intended to enforce responsibility-sharing in matters of asylum claims in cases in which a member states would face a disproportionate number of asylum claims. The principle was simple: each member state is attributed an “adequate” proportion of the total asylum claims lodged in the EU as a function of its GDP and population; once this threshold is exceeded, a redistribution mechanism is automatically triggered so that asylum seekers are relocated to other member states. The mechanism also provided for member states unwilling to relocate to pay their way out of it through a financial contribution of €250,000 per applicant not accepted.

While mandatory relocation may sound like a good idea in principle, the proposal sparked the ire of some member states, notably so-called Visegrád 4 countries (Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia), which have repeatedly voiced their opposition to relocation.

Governments’ worries and citizens’ attitudes towards international protection

Governments’ worries over migration is not a new phenomenon insofar as migration has become a subject of electoral competition, a topic on which one gains or loses votes, and perhaps even elections. That being said, migration and asylum are two distinct policy issues and public attitudes towards migration and towards asylum may very well differ, as recent scholarship suggests. This blog-post poses a series of questions that we try to answer through a survey conducted in the framework of WP6. These questions are:

- Do citizens support international collaboration to protect people facing persecution?

- Do citizens support or oppose relocation of asylum seekers in their countries?

- Would they be willing to accept asylum seekers from a country struggling to handle influxes or would they rather pay so that another country accept them?

In the rest of this post, we provide some evidence on where Europeans stand on the issue. The analysis that follows is based on a survey conducted in 19 EU member states[1]: Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden.

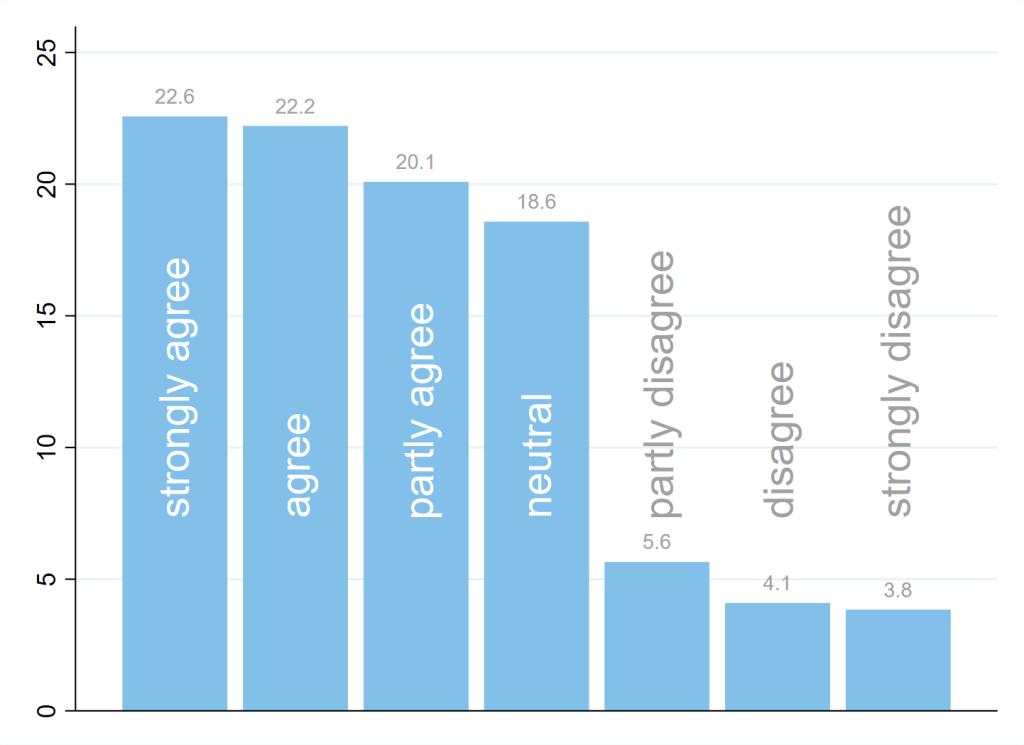

Asked whether countries should collaborate to protect the world’s refugees, an overwhelming share of the respondents answers in the positive: 64.9% of them tend to agree with the statement while a mere 13.5% tend to disagree (figure 1).

Fig. 1. Percentage of respondents agreeing or disagreeing with the statement: “All countries should collaborate and strive by all means to protect the world’s refugees”

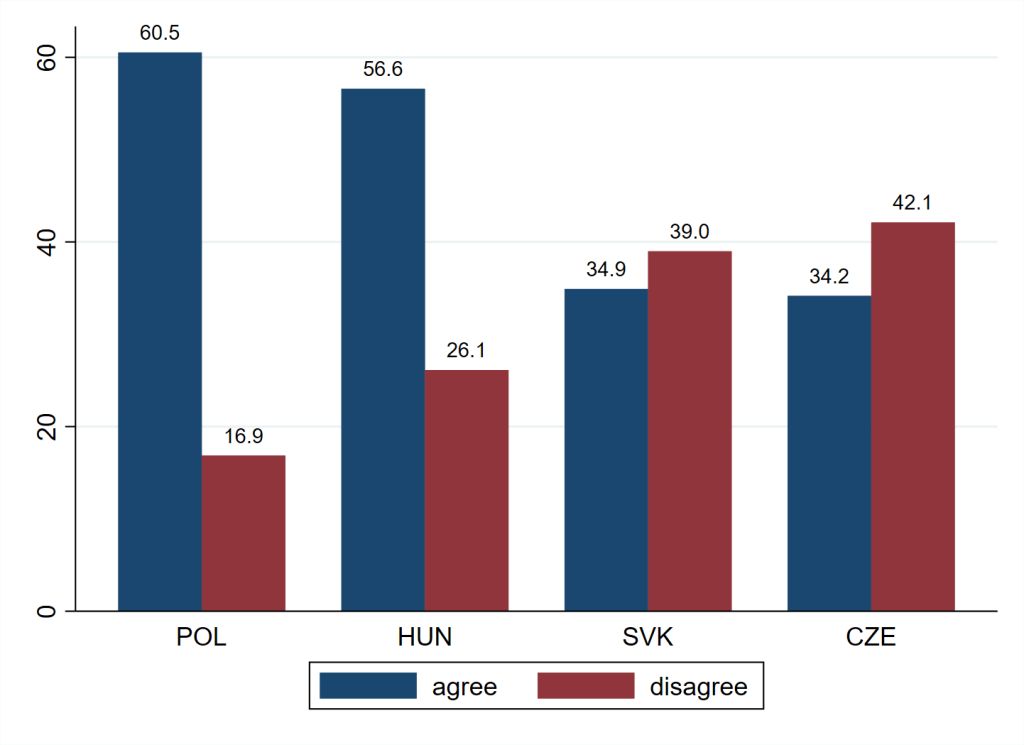

This pattern is similar in most countries under study, perhaps with the exception of the Visegrád 4 countries, which tend to present higher values of disagreement with the foregoing statement (figure 2).

This is particularly the case in Slovakia and the Czech Republic where there are more people disagreeing than people agreeing: respectively 39% and 41% of the respondents disagree with the statement.

Fig. 2. Percentage of respondents in Visegrád 4 countries agreeing or disagreeing with the statement: “All countries should collaborate and strive by all means to protect the world’s refugees”

People’s stance on whether all countries should collaborate in protecting the world’s refugees begs the question of how they would want to collaborate. The statement presented above mentions “strive by all means”, without specifying what those means are. We thus ask the survey respondents whether they would be willing to accept asylum seekers in their country or if they would rather prefer their government pay another country to accept asylum seekers. WP6’s survey, in this respect, conducts an interesting experiment: in asking what respondents prefer, we vary the amount their country would have to pay per asylum seeker in order to have another state accepting them. Respondents are randomly distributed into three groups: the first group is presented with a financial contribution of €5,000 per asylum seeker, the second one with a contribution of €50,000, and the third one with a contribution of €250,000.

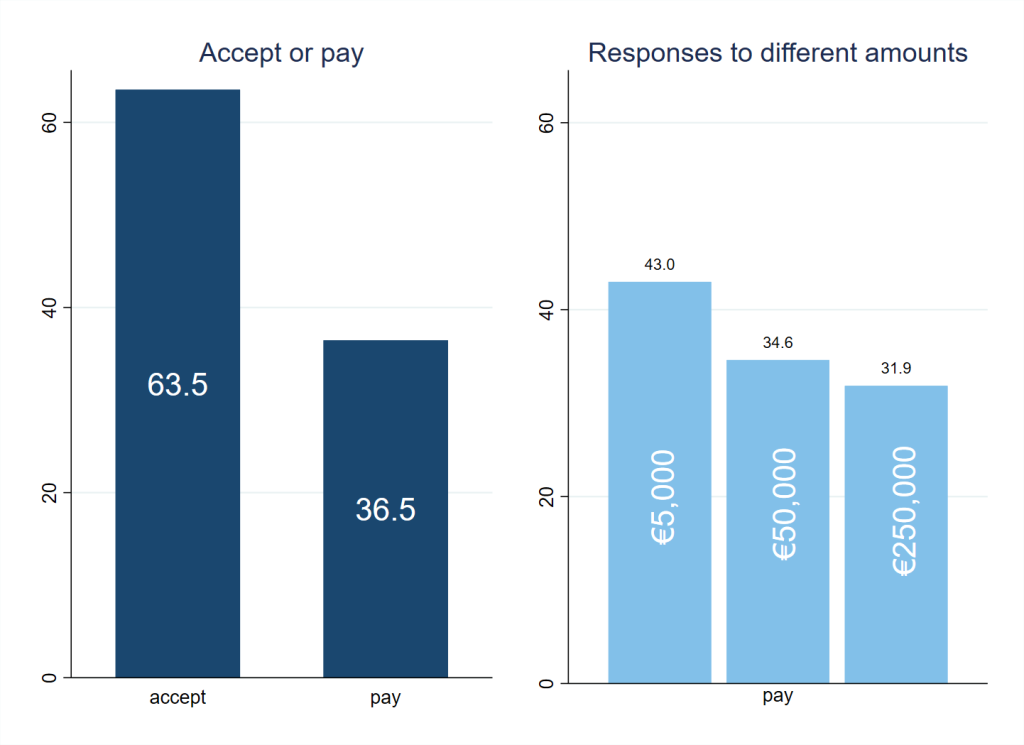

Figure 3 presents interesting results. The graph on the left-hand side displays the overall preferences of respondents[2].

On the whole, a sizable majority of the respondents would opt for accepting asylum seekers in their countries (63.5%) rather than paying another country to accept them (36.5%).

The figure then varies with the amount the respondents are presented with (right-hand side graph): the higher the amount, the more inclined people are to accept the asylum seekers. Where respondents are presented with the choice of either accepting the claimants or paying a financial contribution of €5,000 to the country that accepts them, 43% of the respondents would rather pay (and, thus, 57% would rather accept them). If the amount presented is €250,000, only 31.9% would rather pay than accept the asylum seekers.

Fig. 3. Respondents’ willingness to accept asylum seekers or pay another country to accept them (left-hand side; %); and responses to different amounts presented (right-hand side; %)

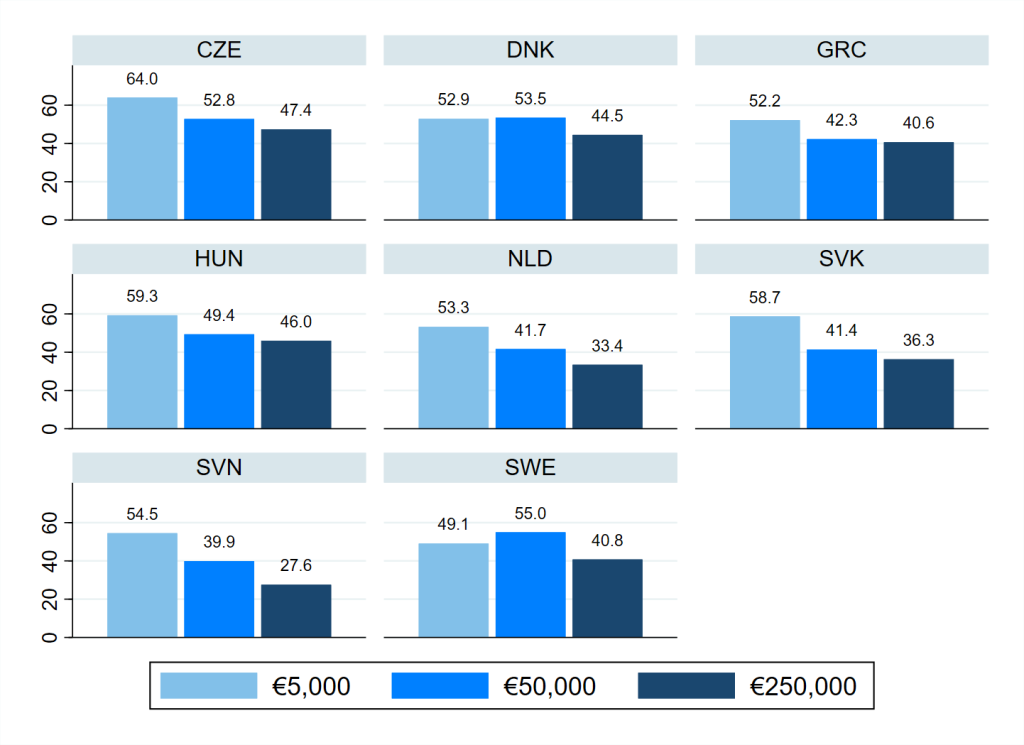

The EU aggregate however hides disparities between countries. People’s willingness to accept asylum seekers is, in some countries, lower than their willingness to pay a €5,000 contribution.

Figure 4 below displays people’s response to the different amounts in countries in which at least one of the amount categories is chosen by more than 50% of the respondents. For instance, in the Czech Republic, a staggering 64% would rather pay €5,000 than relocating an asylum seeker in their country. It is followed suit by Hungary with 59.3% and Slovakia with 58.7%. Note that the Czech Republic and Slovakia are also the two countries in which there is a larger share of people disagreeing with the international collaboration duty than that of people agreeing (see figure 2).

Fig. 4. Responses to different amounts presented in countries with responses over 50%

Conclusion

A large majority of the Europeans surveyed consider that all countries should collaborate to protect the world’s refugees. When asked how international solidarity should manifest – either through admission of asylum seekers or through financial solidarity – they are a majority to be willing to admit protection seekers. Despite the clashes between member states’ leaders during and after the refugee crisis, our preliminary findings suggest that there is significant support in public opinion for more solidarity and, specifically, for relocation within the EU.

[1] This post focuses on EU member states. The survey counts a total of 26 countries; the countries not included in the analysis here are: Norway, the UK, South Africa, the US, Turkey, Mexico, and Canada. All figures presented here are weighted with post-stratification weights. Population weights are also applied where the figures show aggregate of countries.

[2] The graph on the left-hand side serves illustrative purposes and should be considered with caution: since respondents were distributed in three groups which presented them different amounts, they have answered to different questions.