The world is in an uproar following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis on 25 May 2020. In outrage and desperation, demonstrators worldwide have taken to the streets to protest – denouncing the racism and discrimination towards black populations which is still deeply embedded in all layers of society. Racism is also one of the most widespread and devastating experience refugees, asylum seekers and migrants face on their journey to find a new home – and it is alive and well in western countries who take pride in being both inclusive and progressive.

Written by Eva Ecker, Ghent University

Both individuals and institutions are involved in reproducing different forms of racism towards migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees. Currently, asylum seekers in several European countries are victims of institutional racist practices sparked by the Covid-19 pandemic, where heavier restrictive measures have been imposed on asylum seekers than other citizens: many are confined to crowded reception centers while awaiting expulsion or the processing of their asylum claim – or while waiting to undergo compulsory testing. But with Europe’s asylum system on lockdown and expulsion procedures on hold, the Covid-19 detention of asylum seekers has become both arbitrary and inhumane.

These actions are not only unlawful, they also demonstrate unjustified systemic discrimination by leaning on the assumption that asylum seekers as a group automatically pose a greater health threat than other groups, thus contributing to feeding into the pre-existing xenophobic beliefs that foreigners somehow are responsible for spreading the virus.

Xenophobic political campaigns and policy

However, the pandemic is not the only context in which overt European racism prevails. European politicians and activists have been known to openly express and launch ‘contra asylum and refugees’ attitudes and campaigns in newspapers, on tv, the radio, and publicly visible billboards. Some of these political actors have been directly associated with the sitting government, such as the case of the Hungarian government issuing an 18 pages booklets as part of an anti-migration campaign following the refugee crisis in 2016.

In addition to actions of pronounced racism, Europe’s migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees are often victims of subtle institutional racism as well, visible in the UK practice of providing asylum seekers with ID cards looking distinctly different than their country fellows’, thus forcing them to reveal or expose their status in everyday situations.

This labeling has been compared to the obligation of Jews to wear the Star of David during World War Two in order to expose their religious affiliation. Subtle institutional racism towards migrant and refugee populations also pervades the European housing and labor market, manifesting itself in the prejudices of potential landlords and employers who are preventing migrants and refugees from accessing jobs and housing on the same basis as everyone else. Experiences like these are widespread and have recently been reported in several European countries such as Germany, Italy, the UK, and Belgium.

Institutional racism is kept alive by citizens who reproduce it

Both subtle and pronounced acts of institutional racism nourish the dichotomous us-them notion pervading the current public refugee and asylum discourse and prevent the pillars of European society from fulfilling their duties to protect vulnerable groups. However, it is important to point out that institutional racism is kept alive by the citizens that reproduce it.

Institutional racism is merely manifestations of collective acts of pronounced and subtle individual racism. These acts feed into the structures of our societies and consolidate and solidify the ‘us versus them’ discourse that allows the already existing void between country nationals and newly arrived refugees and migrants to grow.

Subtle racist attitudes and individual prejudices are vivid and explicit in several EU member states when studying for instance survey findings, where a high number of respondents answer affirmatively on questions such as ‘refugees will increase the likelihood of terrorism in our country’, ‘refugees are a burden on our country because they take our jobs and social benefits’ and ‘refugees in our country are more to blame for crime than other groups’.

Racial, religious, or cultural slurs as expressions of these prejudices, such as ‘go back to your own country’, are for many asylum seekers, migrants, and refugees part of their everyday lives in both physical and online spaces as members of the European community.

Subtle everyday racism should not be glossed over, but combatted just like violent racism, as both are connected: severe racism does not happen out of the blue, it is often incrementally nourished by subtle racism. As subtle practices of racism are embedded in all facets of society, they are harder to identify. One part of the problem is that many are not aware of how they personally contribute to the problem.

Hostile, violent acts cause and exacerbate trauma

Subtle racism can in some cases serve as bridges and motives towards more severe and damaging acts of pronounced racism, of which there have been many reported cases in recent times: protests against asylum centers, sometimes including arson and vandalism, which have been observed in Ireland, Germany, Greece, and Belgium. Vandals have legitimized their actions by claiming that asylum seekers ‘overflood’ the country, pose a threat to Western norms and values, cost too much money, bring more crime to society, and harm the ‘village identity.’

Some people have compared the burning of asylum centers with the ‘Kristallnacht’ in 1938 where properties of Jews in Germany were massively destroyed in one night of vandalism. Another even more extreme example of contemporary pronounced racism concerns a case of a 17-year-old asylum seeker in the UK who was attacked at the bus stop after he told his attackers he was an asylum seeker, leaving him with a blood clot in his brain and a fractured skull. Unfortunately, similar incidents keep getting reported, including arson, murder, false assault allegations, death threats, harassment, and damage of property.

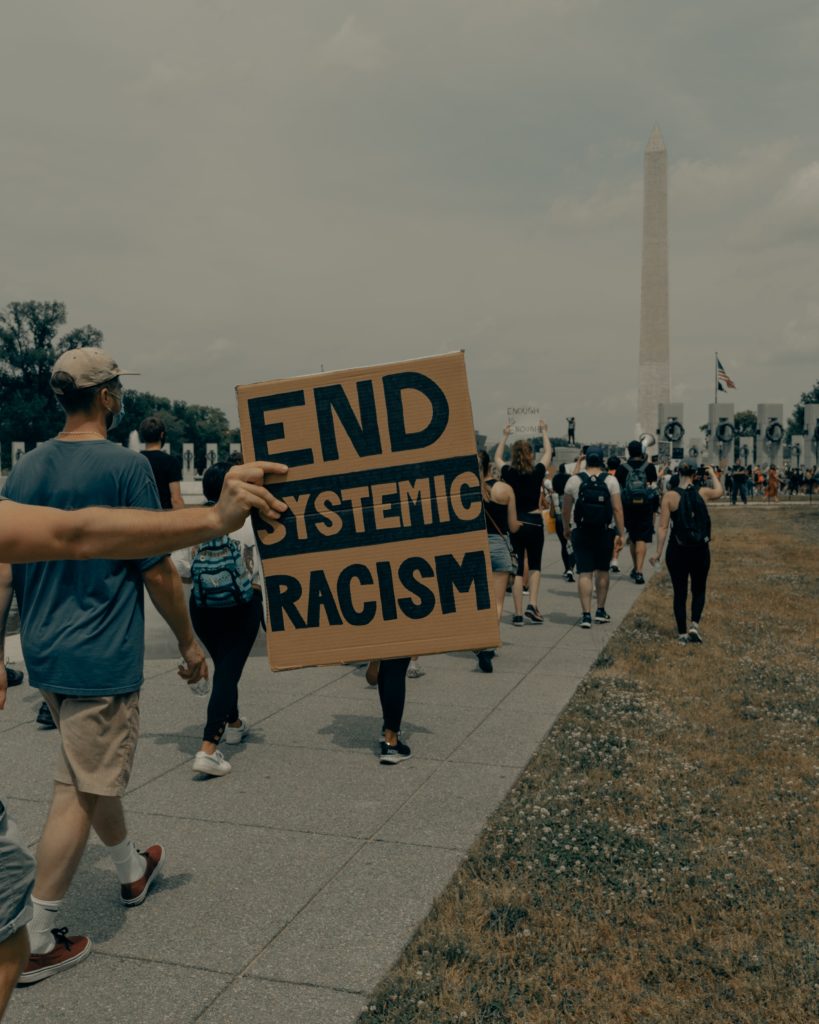

The world has been in an uproar following the death of George Floyd in May 2020. Protests against racism have been documented worldwide. Photos: Aaron Blanco Tejedor and Clay Banks / Unsplash

The severe consequences of racist acts have not only caused physical trauma for migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees in Europe, they have also been documented on mental health, resulting in less sense of belonging, lower levels of trust, reduced sense of control, less hope, anxiety, and trauma.

Racist attitudes and asylum practices also legitimize the of exploitation and abuse of asylum seekers, migrants and refugees, segregation, and more difficulties accessing rights and services. The examples outlined above make clear that the overall protection of asylum seekers and refugees is currently jeopardized because of the re-occurring institutional and individual acts of racism – protection that should be guaranteed both legally and ethically.

How do our actions contribute to reproducing racism?

Racism is a wicked problem caused by multiple actors on multiple levels and needs to be treated that way. In order to grapple with racism towards migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers, we as individuals, policymakers and researchers need to educate ourselves, spread awareness, and find out how we contribute to the problem: firstly, we need to look in the mirror and confront ourselves with how our past words and actions have contributed to building discriminatory practices and institutions and how we are keeping them alive today.

It is not too late to call on the community around us to make both structural and personal changes, but it will require us to listen more carefully to the devastating experiences of refugees and migrants. Their stories, if heard, can spread awareness of how our actions and prejudices currently are contributing to reproduce racism on all levels.

Secondly, we must increase our support for organizations and individuals that combat injustice on the ground by devoting our time and attention to their work. Not only can supporting the work of professional actors in the field of asylum and migration bring about positive concrete changes in our communities, increasing the visibility of their work can also strengthen their role as policymakers leaning on government actors.

Lastly, we can diminish racism by not voting for political actors that in any way wish to maintain institutional racism towards asylum seekers and refugees or that seek to uphold the discourses of “us vs. them”. We need to become educated voters who use our political power to shape a positive public discourse that celebrates diversity and contributes to creating equal institutional opportunities for all groups in European countries.

Battling racism is fundamental in order to enable refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants who have left their country or community to build a good and safe life in the EU. Not confronting and changing our own racist practices is allowing the fear and suffering of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants, albeit in a different way, to continue in places that are supposed to be a ‘safe haven’.

Read more:

Bhatia, M., 2020. Crimmigration, imprisonment and racist violence: Narratives of people seeking asylum in Great Britain. Journal of Sociology.. doi:10.1177/1440783319882533

O’Nions, H., 2010. What Lies Beneath: Exploring Links Between Asylum Policy and Hate Crime in the UK. Liverpool Law Review.. doi:10.1007/s10991-010-9080-y

Pedersen, A., Clarke, S., Dudgeon, P., & Griffiths, B. (2005). Attitudes toward Indigenous-Australians and asylum-seekers:The role of false beliefs and other social-psychological vari-ables.Australian Psychologist,40, 170–178.

Pedersen, A., Hartley, L.K., 2015. Can We Make a Difference? Prejudice Towards Asylum Seekers in Australia and the Effectiveness of Antiprejudice Interventions. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology.. doi:10.1017/prp.2015.1

Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. 2015. “Protection from Xenophobia: An Evaluation of UNHCR’s Regional Office for Southern Africa’s Xenophobia Related Programmes.” UNHCR. https://www.unhcr.org/research/evalreports/55cb153f9/protection-xenophobia-evaluation-unhcrs-regional-office-southern-africas.html (June 4, 2020).

Schuster, L. 2003. “Common Sense or Racism? The Treatment of Asylum-Seekers in Europe.” Patterns of Prejudice 37(3): 233–55.